Homepage

•

Learning Library

•

Blog

•

How we fared when COVID-19 forced us to reinvent learning

Expand breadcrumbs

- Learning Library

- Blog

- How we fared when COVID-19 forced us to reinvent learning

- Homepage

- •

- Learning Library

- •

- Blog

- •

- How we fared when COVID-19 forced us to reinvent learning

How we fared when COVID-19 forced us to reinvent learning

It all felt a bit surreal.

One minute, students were looking forward to spring break. Then COVID-19 flipped the – world on its head. Home became school. Parents became teachers. And teachers became the linchpins in one of the biggest educational experiments in history.

“If anything was ever going to change education, it might be the coronavirus,” says Andrew Smith, chief strategy officer for Rowan-Salisbury Schools in North Carolina. “I think this will forever change the way we think about how we instruct kids.”

When the school closures began, many people thought they would last only a few weeks. Soon, states announced closures for the remainder of the school year. By March, 90% of the world’s enrolled school children were at home due to COVID-19, according to UNESCO.

Like most superintendents across the nation, Carol Kelley, Ed.D., of Oak Park 97 in Illinois, leapt into action when the state closure order came. Her leadership team worked through the night to prepare guidelines for the district’s shift to remote learning. The plan went out to administrators, who spent the next night learning the information front and back so they could deliver it to staff in the morning. By Monday, the district was ready to go online.

“Our staff literally transformed how schooling is normally done in less than 48 hours,” Kelley says. “Every teacher and administrator deserves a presidential award.”

Not everyone made the transition smoothly. For weeks, districts operated in crisis mode, scrambling to make sure students were safe, fed and equipped to continue their learning at home. Then came the mad dash to reopen learning online. Leaders wrestled with equity and connectivity issues, while platforms such as Zoom, Canvas and Seesaw became lifelines for teachers attempting to recreate their classrooms in virtual space.

While districts such as Oak Park 97 pivoted to remote learning within days, others, such as California’s Cajon Valley United, needed a few weeks to reopen online. Districts that had already laid the groundwork for distance learning got a head start, but even those steeped in digital instruction soon found themselves out of their depth as two weeks of home learning stretched into nine.

The questions were overwhelming. How do we feed the children on free and reduced-priced lunch? How do we make sure all students have devices and internet access? Can we provide accommodation for students with disabilities? How do we take attendance online? What does teaching and learning look like without an actual school building?

The pandemic ignited a massive experiment, giving online learning an unexpected trial by fire and changing education in ways we can still only guess at. Now that most schools are closed for the summer, educators who have been working around the clock can finally pause to take a breath and reflect on where to go from here.

“What is this all going to mean, moving forward into the future?” asks Lu Young, executive director of the University of Kentucky’s Center for Next Generation Leadership. “How do we take everything we’ve experienced and figure out what it means for schools and classrooms once it’s safe to go back out again? What key lessons have we learned about what is essential and how to better empower students as owners of their own learning?”

There’s no telling how the massive shift to remote learning will affect students or the way learning is done in the future. But one thing is clear: Technology, integrated to wildly varying degrees in schools across the nation, has become a vital tool for keeping teachers connected to students and each other.

“The idea that we will never again find ourselves forced into fully online mode even for a short time period is untenable to me,” says Joseph South, chief learning officer for ISTE. “We can now expect that in the future there will be times when we will have to shift our mode of learning either partially or fully online, for either a short or long amount of time. What we want to be thinking about is how to develop resilient systems, and do we have the resources we need to do that well?”

Staying connected during lockdown

As nationwide remote learning staggered to its feet, parents in rural North Carolina were flocking to school parking lots to tap into the Wi-Fi. At Rowan-Salisbury Schools, where one of the nation’s fastest digital cities lies just five miles from an internet dead zone, the technology team worked with access point providers to jack up school Wi-Fi signals so students without home access could hop online from the safety of their cars.

“Even though we’ve tried our very best to bridge the digital divide – and we’ve been working on it for six or seven years now – we still really aren’t there,” Smith says.

Getting every student connected was one of the first challenges district leaders faced during the pandemic. According to an Associated Press analysis of census data, an estimated 17% of U.S. students don’t have access to computers at home and 18% don’t have home access to broadband internet. Without it, educators feared learning would come to a screeching halt for underprivileged kids while their more affluent peers continued to progress, widening the learning gap.

The disparities prompted some districts to put the brakes on remote learning. “You cannot open a ‘brick-and-mortar’ school in Oregon unless it is accessible to every student in their school district. The same rules apply to an online school,” Marc Siegel, spokesperson for the Oregon Department of Education, told The Oregonian. “Online learning in a school district cannot be implemented with an ‘access for some’ mindset.”

Many other districts bravely forged ahead, offering digital lessons for those who could access them and supplying the rest with paper packets or other alternatives – anything to keep kids learning. On the last day of school, Baltimore County Public Schools orchestrated a districtwide effort to let every student check out library books, clearing more than 65,000 titles from library shelves.

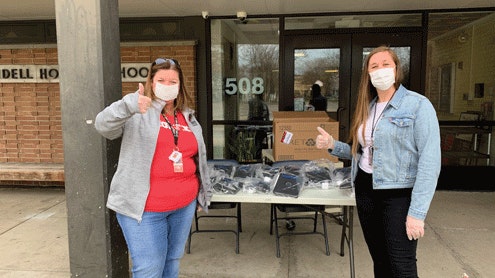

Los Angeles Unified School District partnered with local public TV stations to broadcast educational programming every day from 7 a.m. to 7 p.m. Meanwhile, school lunch pickup sites, which served many of the same students who lacked internet access, doubled as technology distribution centers as districts rushed to hand out as many mobile devices and Wi-Fi hotspots as they could scrape together.

Instead of distributing lunches on school property, Jessamine County Schools in Kentucky enlisted its bus fleet to deliver meals to students. Leaders quickly began exploring ways to embed the buses with technology and other learning resources. In areas that struggle with connectivity, buses could be equipped with Wi-Fi and dispatched as neighborhood hotspots, loaded with mobile devices to hand out or stocked with library books and other paper materials.

“How do those bus deliveries become a place where parents can walk up and say, ‘I need such and such’?” asks Young, the district’s former superintendent. “Delivering those meals provides a safe and distant touch point. Having those buses out there as the new face of the school district provides a way to stay in touch that many families could access.”

That ability to think outside the box and creatively repurpose resources will be essential as educators continue to navigate the pandemic and its impact on underprivileged students, she believes.

“I don’t think there’s anything that’s not on the table at this point. This is a time when creativity and resourcefulness are at a premium. How are we thinking about all of our resources and using them for multiple purposes?”

Helping kids process the pandemic

While educators grappled with connectivity issues, students were enjoying what felt like a prolonged snow day. But as stay-at-home orders became more urgent, the realization hit: There would be no last-day-of-school parties or yearbooks to sign. Sports seasons, proms and graduations were called off. Many students didn’t even get to clean out their lockers.

“It was kind of sudden for me,” says Sorrin Garcia, a sophomore at Camelback High School in Phoenix. “I was there one day, expecting to come back a week later. Now we’re not going to go back at all. It caught all of us off guard.”

Sadie Bograd’s prom dress still hangs on the attic door, unworn. “Hopefully, it will last until next year,” says the junior at Paul Laurence Dunbar High School in Kentucky. In a climate dominated by alarming death tolls and horrifying images from hospitals across the country, she admits it feels a little selfish to mourn the loss of prom. But for the 1.5 billion learners in more than 160 countries affected by school closures, anxiety over the global pandemic coexists with feelings of disappointment, frustration and loss at being disconnected from friends and missing out on irreplaceable rites of passage.

“I worry that there’s a sense that the most important thing to do right now is to focus on academics and get kids learning, and we’re not dealing with this collective punch to the gut,” says former district superintendent Joshua Starr, CEO of PDK International. “We have multiple punches to the gut coming our way. Our most important job is to attend to kids’ emotional needs, their confusion and concern. We’ve got to give space for that, and schools have to balance that.”

Social distancing has been hard on students who are used to seeing dozens if not hundreds of people flow through their lives daily. One thing the pandemic has highlighted is the multifaceted role schools play in children’s lives; they’re social hubs and emotional support systems as well as places of learning. In making the shift to distance learning, educators discovered the importance of meeting students’ social and emotional needs as well as academic ones – especially in a crisis.

While district leaders focused on getting lunches out and drafting protocols for distance learning, teachers took the lead on reaching out and offering reassurance to bewildered students. They teamed up on Zoom to record encouraging music videos. They left personal messages in sidewalk chalk outside students’ homes. They decked out their cars and paraded through school neighborhoods.

To address students’ psychosocial and emotional needs during the shutdown, Baltimore County Public Schools assembled a team to explore how school counselors and social workers can leverage the same instructional tools as teachers to provide emotional support for students.

“It’s one of the things we’re talking about whenever possible,” says Ryan Imbriale, executive director of the district’s department of innovative learning. “All these resources can also be packaged to help providers working in the system provide emotional support. School counselors may be able to use Google Meet to talk with students who need that support. We are trying to look broadly at opportunities beyond just instructional.”

For Sorrin, just hearing daily from teachers has made a difference.

“My teachers are constantly checking in to see if I’m OK, if I need anything, if I’m staying sane. It’s good to hear from them even if I’m not seeing them every day. The connection is not as strong as it used to be, but I know they still care about me.”

From crisis mode to high-quality learning

While students lamented the loss of prom, many educators were celebrating the cancellation of another big event: spring standardized testing. In March, the U.S. Department of Education waived federal testing requirements for all 50 states. Several states went a step further, announcing that online work wouldn’t count toward students’ grades.

The closures impacted the Keystone Academy in Beijing several weeks ahead of what was happening in the U.S. As online learning days extended into months in China, Sandra Chow, Keystone’s director of innovation and digital learning, says the school took the opportunity to remember it’s mission.

“We began making priorities based on the core principles of our school,” she writes in her Global Focus column on page 43. “This meant that our learning embraced inquiry and real-life connections, we emphasized character development through online interactions, designed assessments with process and feedback in mind, and celebrated and encouraged service learning.”

Some in the U.S. also began to see an opportunity in the crisis. Freed from the shackles of standardized testing, they could explore the limits of what online learning could be.

“Let’s do education like we’ve always wanted to,” Smith says. “We’ve got an awesome opportunity to try something new. Let’s look at problem-based learning, where you find a problem for kids to solve and give them a few days to do it, instead of drill and kill.”

But most districts were still operating in crisis mode, with teachers struggling just to provide instruction – any instruction at all – to ensure learning continuity during the pandemic. The result, ISTE’s South says, is that the bar for online learning has been set far too low.

“It’s troubling, because we can’t let this be the floor for what we think online learning needs to be for our schools,” he says. “The danger is that people will start to believe that this is what online learning is, and they won’t be motivated to really step back and think about what it could be, to realize its full benefits.”

Now that districts have moved past their initial crisis response, it’s time to start asking what quality online learning should really look like, he says. While pedagogy for distance learning, blended learning and online learning have all been called upon to meet this moment, none is a perfect fit for what educators collectively experienced this spring.

For Ohio’s Lakota Local Schools (LLS), a suburban K-12 district with 17,000 students, successful online learning starts with flexibility. Todd Wesley, LLS chief tech-nology officer, worked with the district’s leadership team to develop a Remote Learning Resources Guide, which opens with the words, “We must plan for flexibility, not perfection.”

During the pandemic, teachers delivered instructions via video as well as text, asynchronous learning and playlists to accommodate differing family schedules. They also assigned both digital and nondigital work, which might mean hands-on science activities, such as drawing a map of the students favorite neighborhood walk and identifying plants.

The district provided professional development for existing and expanded tools so teachers could integrate flipped lessons; live and recorded video options; and content creation, curation and sharing. Rubrics and checklists helped keep students on track and engaged, allowing teachers to focus on the most important learning outcomes instead of providing busywork.

“With the whole world part of this sudden shift to remote learning, quality of learning will certainly be a primary consideration, and I anticipate new indicators and assessments, and new approaches to students’ demonstration of learning, will be developed,” says Wesley. “We are going into this with our longstanding expectation of quality, but with an understanding that flexibility and an open mind are critical as we navigate these uncharted waters.”

Training for educators was, and will continue to be, a critical component of making a successful shift, says Michele Eaton of Metropolitan School District of Wayne Township (MSD) in Indianapolis. When the school closure order was announced for Indiana, the district was already in the process of approving a virtual school plan for inclement weather, although it had not yet been tested. MSD went fully remote for its 17,000 students within 48 hours.

Eaton, director of virtual and blended learning, says MSD already used virtual and blended learning courses, designed in-house, and quickly developed a remote learning guide, which provided a template for what quality learning looks like. Teachers then had two planning days to prepare.

The district hosted live and recorded virtual trainings twice a day on topics ranging from how to use the tools to keeping students engaged and making lessons accessible for all. With both live and recorded sessions, teachers could choose sessions that were convenient for them or attend a live session if they needed more individualized help.

“In our district, we feel strongly you can design online learning that is just as effective as classroom learning,” says Eaton. “We think that for the majority of our students the best environment is more traditional with blended components. There is value face to face, but also know this was an emergency situation and we will keep improving.”

Solving accessibility challenges

While face-to-face instruction is an important element for all students, there is no population for whom that’s more true than students with disabilities such as autism, deafness or learning disabilities. Serving these students, who make up roughly 4.6% of all public school enrollment, continues to be one of the thorniest issues facing schools.

The U.S. Department of Education relaxed the requirements for serving these students during the crisis, but Torrey Trust, associate professor of learning technology at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, says we can and should continue to educate all students so that none are left behind.

“The point of public education is to try to provide equal footing,” says Trust. “It doesn’t have to be perfect in this emergency situation, but I want to see educators be creative in these times. Instead of shutting down, use technology as a resource.”

Trust developed a slide deck, rooted in Universal Design for Learning (UDL), with seven things to consider as educators moved quickly to set up emergency remote learning. The basics of UDL include allowing for multiple means of representation, engagement, expression and action. This can be as simple as making video transcripts available for students who cannot hear or allowing students to choose whether to answer a question in writing, video or through an art design.

Open educational resources (OER) can help educators find creative solutions for students with special needs. Because they’re available in the public domain or introduced with an open license, educators can remix them as needed.

The flexibility of OER makes them easy to adapt for UDL purposes. In addition, OER listed on the MASON OER Metafinder, OER Commons or OASIS have been vetted for privacy or accessibility and are rated for quality.

“I’m hoping we can shift to UDL, whether high tech or low tech, because it will be so beneficial for making more inclusive learning environments at home as well as when students get back to the classroom,” she says.

What comes next?

The COVID-19 pandemic has prompted a burst of innovation and self-sacrifice, from the robotics team at Oregon’s South Eugene High School that designed and fabricated face shields for those on the front lines to the countless teachers providing meaningful learning for students while homeschooling their own children. But has it been enough?

It’s hard to know where we’ll be in the fall. A new study from NWEA indicates that “compared to how much they would have learned in a normal school year, elementary and middle school students are likely to start school in the fall with only about 70% of those reading and writing skills, and with 50% or less of the expected gains in math.”

That staggering amount of learning loss will take years to make up, experts say, with the burden falling disproportionately on students whose families are least equipped to help them regain lost ground.

The pandemic has exposed many gaps in our societal systems, from health care to schools. Aside from becoming better prepared for similar emergencies in the future, we’re seeing more clearly all the ways that schools serve students – and the ways they don’t. Freed of the way we did things before COVID-19, we can start questioning why we did them in the first place.

“I think there is an opportunity, even when we go back to the classroom, to ask ourselves, ‘Can learning be more mastery-based, more in tune with the interests of students, more open to the ability to investigate using online tools? Can it be more open to using tools to create an expression of what they’ve learned that’s the best match for them?’” South says.

Already, we’ve been forced to think creatively and make technology accessible to all students. What if we decide that a bell schedule and seat time are not as essential to learning as progress and understanding? What if we all return to the classroom with the spirit of innovation and cooperation learned during this crisis?

If we accomplished this much with technology during a pandemic, what could we achieve with it in more ordinary times?

“We don’t have to leave technology behind the emergency glass,” South says. “We can pull it into the classroom to enhance learning and also build resiliency. I hope in the long term educators and education leaders will think about how to build in resiliency and make this part of what we do – not a life preserver, not a tasteless emergency ration, but something that’s part of our regular diet.”

Tales from the front lines

Here’s a glimpse at how some districts leveraged past initiatives and new approaches to keep learning going.

Lakota Local School District, Ohio

It’s a typical school day at the Bauer house in Liberty Township, Ohio. Third grader Riley has been working on math and reading most of the morning. Afterward, she’ll take a break to do some sidewalk chalk outside. She’s looking forward to a special afternoon project assigned by her teacher, Kelly Scarbrough.

When COVID-19 closed schools, Scarbrough’s class at Cherokee Elementary had been studying butterflies and insects. While still in school, the class learned about moths in England that can change color to camouflage with surrounding trees. The class cut out moths and colored them to match things in the classroom, then hid them for classmates to find.

On an afternoon during school closures, Riley camouflaged moths with her little sister, Emily, who is in kindergarten, then the family had a moth-hunt around the house to see how well they did.

Lakota Local Schools, a suburban K-12 district with more than 16,700 students, has valued personalized learning since the 2018 implementation of WEareEMPOWERED, a 1:1 initiative for grades 7-12 that included embedded technology and personalized learning in all its schools.

During the pandemic, that program empowered students to be leaders in their own learning from home.

“In the district, there has been lots of movement toward personalized learning and that has helped this move to remote learning along,” says Riley’s mother, Katie Bauer. “Because students are comfortable with having a choice in how to learn a concept, they are comfortable in figuring out how they want to execute that learning.”

The district watched as closures due to COVID-19 made their way across the world. In preparation, the district created a Remote Learning Resources Guide and held one practice remote learning day before closing its doors. The practice day let the district gather feedback and make adjustments.

“All district leaders realize this will be an evolution and flexibility and adaptability will be key,” says Todd Wesley, LLS chief technology officer. “Starting slowly and simply is critical to building a solid foundation.”

The resources guide lists some key principles in their vision of remote learning, such as flexibility; a focus on the most important outcomes; being accessible to all learners, not a duplication of in-person learning; and both digital and nondigital learning.

Each week this school year, Scarbrough assigned Riley and her classmates math “playlists” or assignment options, to choose from. Students do all the assignments, but in the order they choose. Some prefer to start with the harder ones, some the easier. Emily’s kindergarten teacher used a choice board where the student can choose which version of an assignment to do.

The groundwork in personalized learning made the transition to remote learning easier, says Scarborough. The Remote Learning Resources Guide provided district-approved resources to help close the gap between her home and her students’ homes, and specified how to keep good teaching practice when you’re not face to face.

For instance, to keep learning accessible to all learners, she gave directions in text and videos, and shared examples so that students can work more independently without her presence for immediate feedback.

Scarbrough’s class was scheduled to begin a spiral review of math for the year when they went to remote learning. It quickly became obvious that this wasn’t going well for some learners. She posted a hint and a help video for every single question. This is a change she will keep even after they are physically together in the classroom again.

Emily’s kindergarten assignments had an electronic option and a nonelectronic option. The girls’ mother, Katie, says the hardest part of distance learning was that she and her husband continued to work from home, while trying to help with school for Riley and Emily. Riley stepped up to help her sister. For example, one day the two hunted for shapes around the house, one assignment from Emily’s class.

Next, Scarbrough’s students learned about the Wright Brothers. While they did some of the learning by reading or listening through the digital classroom, the project at home was building paper airplanes and graphing which designs fly the furthest.

“We went into this with our long-standing expectation of quality, but with an understanding that flexibility and an open mind are critical as we navigate these uncharted waters,” says Wesley. “We can ensure quality is maintained, it may just look or feel different … and that’s OK.”

Oak Park District 97, Illinois

On the first day of remote learning in Oak Park, Illinois, first grader Brooks Gerace walked downstairs, put his hand on his heart and started saying the Pledge of Allegiance. His family burst out laughing. But Brooks wasn’t trying to be funny. “I was just trying to make my day feel better,” he says.

Brooks and his sister, third grader, Ruby, attend Irving Elementary School. They thought that their principal, John Hodge, should continue to do the announcements during remote learning. Then, they had an idea. They would make the announcements.

Brooks began standing in for Mr. Hodge each morning, announcing birthdays, saying the pledge and giving the lunch menu (“Whatever is in your freezer!”). Ruby made guest appearances as the assistant principal. The pair posted their daily videos on the school’s Twitter feed.

“The response has been great,” says Hodge.” People appreciate the sense of normalcy and the opportunity to laugh during these times.”

The PK-8 district with 6,000 students implemented a plan five years ago that emphasized personalized learning and provided a device and at-home internet for every student grades 3-8. In addition, the district was in the process of approving an inclement weather plan allowing for remote learning. Although the plan had not been approved or implemented, when the order for closure came the district was able to build off that plan to transition quickly.

On Thursday, March 12, the Illinois governor issued guidance to restrict large gatherings and District 97 decided to close. The central office team worked all night to prepare professional learning decks, which were shared with staff the next day during an emergency Institute Day. Staff then did their own preparation over the weekend and were ready to go by Monday.

“They literally transformed how schooling is normally done in less than 48 hours,” says Oak Park District 97 Superintendent Carol Kelley, Ed.D. “Whoever can give that presidential award, every teacher and administrator deserves that.”

The focus and foundation of the plan is connection. The district has a team of instructional coaches, one for each of its 10 buildings, who provided remote professional development to help teachers become more proficient with the tools of connection. Using Zoom, Canvas, Seesaw or other platforms, teachers connected with their students and each other to build a sense of community and focus on each other’s social and emotional needs.

Irving Elementary teachers stayed connected with students by recording read alouds and using Padlets to share responses to questions. Many of Oak Park’s educators and students are comfortable with technology because integrating it into instruction has been a focus at the district. For example, the Lincoln Tech Club is a student-organized and -facilitated club. The club’s more than 80 fifth grade students teach staff members and other students how to use technology when doing projects.

“Brooks demonstrates the level of comfort our students have with taking a leadership approach,” says Kelley. “Had it not been for prior learning experiences, I don’t know if we would have seen students taking that kind of leadership.”

Ruby missed her friends and her teacher at school. During remote learning, she worked on a slideshow about killer whales. As her father spoke about their new normal over Zoom, Ruby reached over to fiddle with the screen. Suddenly, there’s a killer whale swimming behind her on the screen.

“As the adults, we have to know how to label the emotions we are experiencing and model for our students,” says Kelley. “I think we will get through this crisis, but our goal is to get to use self-reflection to get to the other side of doing things that are more creative and innovative than we were going into it.”

Cajon Valley Union School District, California

Cajon Valley students were out of school for five weeks before they returned to school online. The district, which serves just over 17,000 K-8 students and has a 70% free and reduced-price lunch rate, made an intentional choice to focus on fostering individual relationships rather than rushing to begin remote learning or maintaining strict measurements of academics that were in place before the closures.

By choosing to place all its students in small advisory groups led by a single teacher, the district stayed true to its philosophy, “Happy kids, healthy relationships, on the way to gainful employment.”

“When this is all over, we are going to learn what our students love most about school – and it’s not going to be the content,” said David Miyashrio, superintendent of Cajon Valley Union School District, in an article he wrote for District Administration. “It’s going to be the people who take a deep, abiding interest in them.”

The district was well positioned to make the move as it has focused on personalized and blended learning since going 1:1 in 2014. One of the district’s middle schools piloted an advisory program beginning this school year before the closure. Students were assigned to an advisory group and teacher all three years of middle school, enabling the group to form close relationships. The advisory group welcomes students when they enter sixth grade and celebrates their eighth graders when they graduate. In preparing for remote learning, the district placed each middle and high school student with an advisory teacher.

The district’s decision to move all students to an advisory family as part of the transition to remote learning was, in part, in response to requests from families. Parents asked the district to keep school manageable for those who are still working. Rather than receiving assignments from five or six different teachers, one teacher helps 25 kids navigate a playlist of assignments.

The benefit, says Miyashiro, is that if kids trust adults and have good relationships with them, they’re more inclined to be successful. After all, if they don’t like what is happening on the other side of their Chromebook screen, they can just close it.

Choleanne Dilgard, a fourth grade teacher at Cajon’s Fuerte Elementary, appreciates the district’s approach. Dilgard was teaching her students online, as well as supporting her own children at home. She functioned as the advisory for her class, as well as part of the reading team that develops reading lessons and offered support.

The arrangement allowed Dilgard to streamline her job. Content area teachers work together as a team to develop playlists. If the whole math department works together, for instance, that means an individual teacher only has two hours of work out of the six it takes to pull together the playlist.

The relationship helps teachers identify student challenges, customize playlists in response to student needs and develop closer relationships with their advisory students.

“We have to remember, we are not just in distance learning,” she says. “We are in crisis learning.”

Family representatives were active participants as the district developed the plan. Parents requested flexibility, such as a weekly playlist instead of daily assignments. They also asked for activities they could do together to facilitate conversations within the family. Some examples are optional family craft activities or questions for students to ask parents about their first job.

Miyashiro says the focus on flexibility and student-centered learning is something that can benefit districts long past the pandemic. “Most of us recognize that the education system has been in need of disruption for years,” he says. “As education leaders, we need to see this crisis as our chance to do more than simply return to the status quo. Instead, let us seize this opportunity to reorient ourselves to the real challenge we face: helping our children achieve brighter futures in a radically transformed world.”

Rowan-Salisbury Schools, North Carolina

Ten days before his district shut down, Andrew Smith saw it coming. Since growing alarmed about COVID-19 in late February, district leaders had been having cursory conversations about what they might do if they had to do something different with their 20,000 students. At first, the talk revolved around whether to cancel field trips. In early March, the district became one of the first in North Carolina to cancel all its field trips; a week later, the rest of the state followed suit.

That’s when Smith made the strategic decision to start monitoring some of the more forward-thinking states and districts. He noticed that things tended to happen in California about 10 days before they hit North Carolina, almost like clockwork. So when Los Angeles schools closed in mid-March, the chief strategy officer had one week to get everyone ready.

District leaders leapt into planning mode. If teachers had just one more week left with students, what did they need to accomplish in that time? The district already had six years with 1:1 iPads and Macbook Airs under its belt, and teachers had begun pivoting to e-learning on snow days, stockpiling two days’ worth of lesson plans that could be done either synchronously or asynchronously. But that wouldn’t be nearly enough.

“We were kind of set up for (distance learning), but nowhere near what was coming,” Smith says. He gathered all of thedistrict’s curriculum and technology teams together in the central office, where they raced to develop protocols for long-term distance learning. Taking care not to cause a panic, they deployed a survey to all 20,000 students to identify those who lacked internet access at home. With 90% of students connected, they started working on solutions for the other 10%, handing out 300 MyFi hotspots by the last day of school.

“We were really the only people preparing,” Smith says. “At a meeting, I asked someone from another district, ‘Are you preparing?’ They laughed at me.”

Friday was a teacher workday, with professional learning sessions planned at various schools across the district. Leaders ditched all of them. Instead, they told teachers to spend the time developing 10 days’ worth of online lessons. It was a risky move; by Friday afternoon, the governor still hadn’t closed schools, and Smith began to wonder if all that work had been for nothing.

The announcement came on Saturday: School was canceled, effective Monday.

“That started a mad dash of work,” Smith says. “Up until that point, we had just been planning. But planning and implementing are vastly different. We met around the clock. We developed an emergency planning team that includes all key department heads and some of our community principals, and we all sat in a room for 12 hours until we went from having a plan to ‘this is how we implement it.’”

Within a week, distance learning was up and running. While other districts across the nation were still scrambling to pull something together, Rowan-Salisbury was already working out the kinks. For starters, they realized that online learning doesn’t necessarily have to mean sitting down for instruction every day from 9 a.m. to 3 p.m.

“We quickly changed our school week,” Smith says. “Five days in a row is too much. Parents can’t handle it, and teachers can’t handle it. Teachers were getting a lot more work to grade beyond what they would normally do in class. They were working around the clock. They would plan at night and try to do synchronized stuff during the day.”

In response, the district implemented Wellness Wednesdays to give teachers a midweek workday and students a day off. Teachers were also encouraged to explore problem-based learning models, providing students with a problem and giving them a few days to solve it while checking in periodically to make sure they stay on track.

When you’re leading in crisis mode, one of the first things you realize is that everything is subject to change.

“There were times when things were changing hourly for us, and we had to be nimble.” Smith says. “But if there’s one thing we’re used to, it’s change. In this type of environment, people feel comfortable enough to make a decision and maybe have to reverse course.

“We’re learning from failing forward.”

Nicole Krueger is a freelance writer and journalist with a passion for finding out what makes learners tick. from her home in the northwest, Jennifer Snelling (@jdsnelljennifer) writes about educators using technology to empower students and change the way we learn.