Homepage

•

Learning Library

•

Blog

•

Kimberly Eckert Is Passionate About Empowering Diverse Educators

Expand breadcrumbs

Expand breadcrumbs

- Learning Library

- Blog

- Kimberly Eckert Is Passionate About Empowering Diverse Educators

- Homepage

- •

- Learning Library

- •

- Blog

- •

- Kimberly Eckert Is Passionate About Empowering Diverse Educators

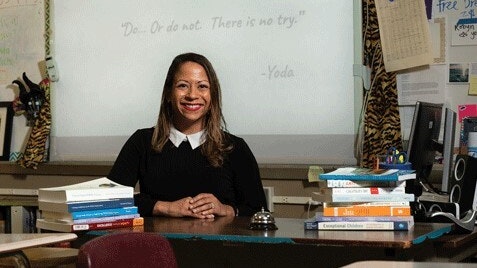

Kimberly Eckert Is Passionate About Empowering Diverse Educators

By Julie Phillips Randles

October 27, 2020