Homepage

•

Learning Library

•

Blog

•

How Remote Learning Brought Out Creative Thinking in Schools

Expand breadcrumbs

Expand breadcrumbs

- Learning Library

- Blog

- How Remote Learning Brought Out Creative Thinking in Schools

- Homepage

- •

- Learning Library

- •

- Blog

- •

- How Remote Learning Brought Out Creative Thinking in Schools

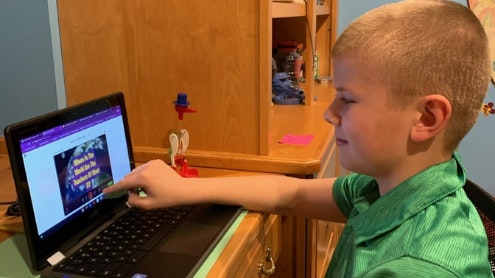

How Remote Learning Brought Out Creative Thinking in Schools

By Jennifer Snelling

April 1, 2021