Homepage

•

Learning Library

•

Blog

•

Leading change: Teacher leaders are catalysts for education transformation

Expand breadcrumbs

Expand breadcrumbs

- Learning Library

- Blog

- Leading change: Teacher leaders are catalysts for education transformation

- Homepage

- •

- Learning Library

- •

- Blog

- •

- Leading change: Teacher leaders are catalysts for education transformation

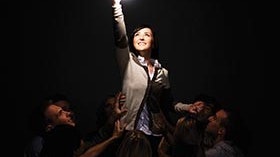

Leading change: Teacher leaders are catalysts for education transformation

By Gail Marshall

July 14, 2015