Homepage

•

Learning Library

•

Blog

•

Some Students Pursued Passion Projects During the Pandemic. What Happens to Them Now?

Expand breadcrumbs

Expand breadcrumbs

- Learning Library

- Blog

- Some Students Pursued Passion Projects During the Pandemic. What Happens to Them Now?

- Homepage

- •

- Learning Library

- •

- Blog

- •

- Some Students Pursued Passion Projects During the Pandemic. What Happens to Them Now?

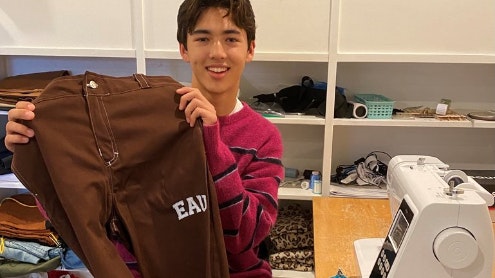

Some Students Pursued Passion Projects During the Pandemic. What Happens to Them Now?

By Jennifer Snelling

November 1, 2021