Homepage

•

Learning Library

•

Blog

•

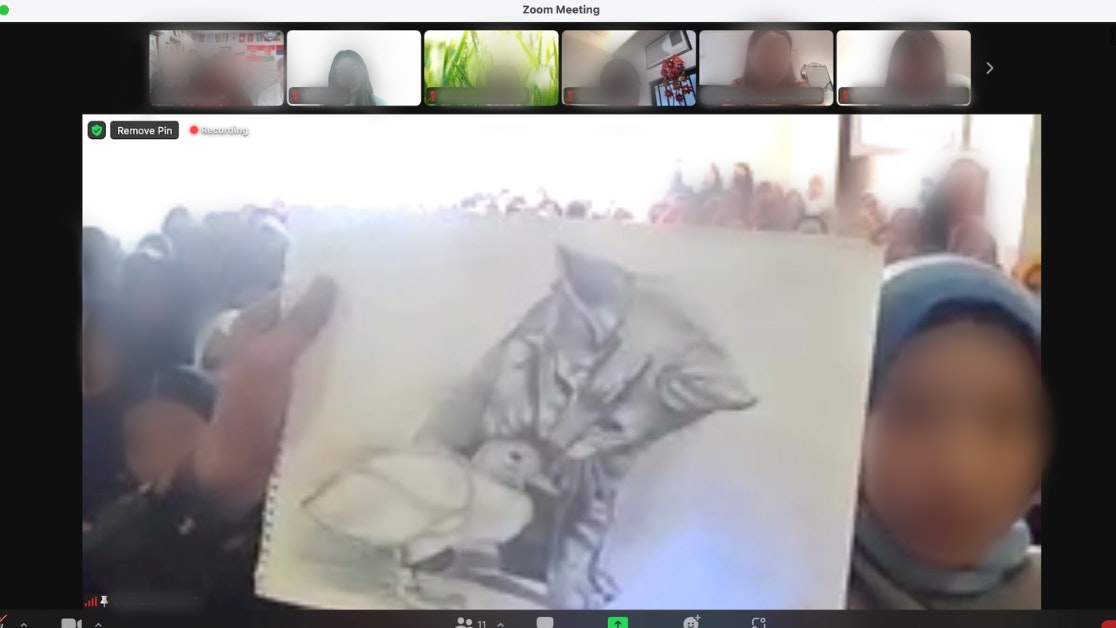

Students Become Teachers To Help Afghan Girls Learn

Expand breadcrumbs

Expand breadcrumbs

- Learning Library

- Blog

- Students Become Teachers To Help Afghan Girls Learn

- Homepage

- •

- Learning Library

- •

- Blog

- •

- Students Become Teachers To Help Afghan Girls Learn

Students Become Teachers To Help Afghan Girls Learn

By Jennifer Snelling

January 26, 2023